More like the diary of Waseem Rizvi – Beyond Bollywood

The contrasting perspectives on two sets of refugees inadvertently support the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act. While there are no issues with the political stance, the film lacks creativity.

Rating: ⭐️ (1 /5)

By Mayur Lookhar

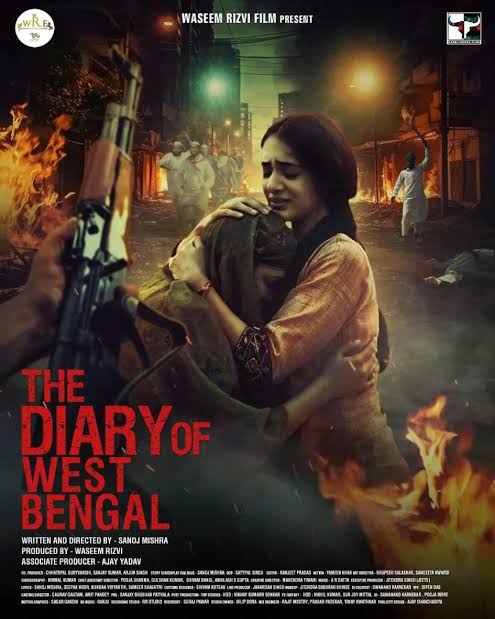

In the times we live in, how can a socio-political thriller film avoid controversy? There was even drama before the premiere as the makers grappled with demand exceeding supply. Compared to the struggles producer Jitendra Narayan Singh Tyagi faced just to get this film released, last night’s (29 August) events seem petty. The film made headlines for its controversial plot, but is the hype justified?

Chaos is the word that preceded the release of this film, and chaos abounds in its narrative. The story begins with empathy for persecuted Hindus in Bangladesh but takes on a few indifferent layers with the action in the Sundarbans, bordering Bangladesh and India.

Bangladeshi Suhasini (Arshin Mehta) and a few other Hindu women are abducted by a Muslim mob, raped, and kept as slaves. A local Muslim man offers them an escape route through illegal migration to West Bengal, India. The women believe the worst is over, but the events that unfold in the Sundarbans leave very few survivors.

It is nothing short of a miracle that Suhasini finds an unexpected saviour in Prateek (Yajur Marwah), a writer and photographer who rather bizarrely emerges from the darkness in the Sundarbans. He assures her that he means no harm and takes her to his home in Murshidabad, West Bengal.

According to the 2011 Census, the area has a majority Muslim population of 66%, with Hindus at 33%. For a Bangladeshi Hindu, it’s surprising how long it takes Suhasini to realise she has gone from the frying pan into the fire.

Writer-director Sanoj Mishra and producer Jitendra Narayan Singh Tyagi (formerly Syed Waseem Rizvi) have been quite defiant in their media interactions, dismissing the word “propaganda.” We, too, don’t subscribe to that label, but the contrasting perspectives on two sets of refugees inadvertently align with the current Indian establishment’s vision of the Citizenship Amendment Act. Adding the religious ideological differences, this film feels more like it’s straight out of Waseem Rizvi’s diary than any diary of West Bengal.

With nine names listed on the film’s CBFC certificate and an A rating, it still remains a dangerously divisive narrative. Before discussing creativity, we should examine the film’s concerns about vote bank politics in the region, particularly Murshidabad. While the 2021 Census is still being processed, if the Muslim population was 66% in 2011, it’s reasonable to expect the community to lead the demographic chart in Murshidabad. Basic research suggests a Muslim population of around 6.6 million, compared to 1.2 million Hindus. For the entire state of West Bengal, the 2011 Census shows approximately 70 million Hindus and 25 million Muslims.

Radical Islam and forced conversions are realities, but if Hindus still constitute the majority population in West Bengal, then issues in Murshidabad should be viewed as isolated cases. Moreover, this challenges the myth of minorities overtaking the majority in West Bengal. While numbers are documented on paper, it’s the ground reality that truly matters. Only the people of Bengal can provide the real picture.

The social and religious crisis in areas like Murshidabad can be viewed in two ways: either the state government is ignorant or it is engaging in vote bank politics. Sanoj Mishra and Jitendra Narayan Singh Tyagi’s film adopts the latter perspective but cautiously avoids naming individuals, simply referring to the chief minister as ‘madam ji’.

Given its subject and ideology, The Diary of West Bengal could have been timelier if released before the 2021 West Bengal Assembly Elections or within the permissible period before the Lok Sabha Elections. However, the current coalition government at the Centre changes the dynamics, making it challenging for the film to receive backing similar to The Kashmir Files (2022) or The Kerala Story (2023).

What may work in its favour is the ongoing crisis in neighbouring Bangladesh, where Hindu minorities face severe threats. Thus, the early scenes depicting persecuted Hindus in Bangladesh and human rights violations in the Sundarbans will likely resonate with a largely Hindu nation like India. The cries of Ragini (Reena Bhattacharya) will echo across nations and evoke memories of 1971. But once the action shifts to Murshidabad, The Diary of West Bengal devolves into a religious debate. The film condemns forced conversions, but its “us versus them” narrative might appeal to ultra-nationalists only. Also glorifying any religion is not what cinema should be about.

One still can’t fathom how, in just a matter of weeks, a Bangladeshi illegal migrant can transform into a vanguard of Sanatan Dharma and show such affection towards India. Social and political goals aside, Sanoj Mishra and Jitendra Tyagi’s film is far from creative. Mishra, with no notable previous work, only underscores his lack of writing and directing skills in The Diary of West Bengal. There is a story, but no coherent screenplay. One must pity the editor who had to endure poorly shot scenes, a disorganized screenplay, and subpar performances.

Young Arshin Mehta partly reminds of forlorn actor Tara Sharma, with a somewhat similar tone, though not as grating. Suhasini’s pain and struggles help her find strength, eventually leading her to stand up against radicals in Murshidabad. Sanoj Mishra aimed to portray Suhasini as a Durga, but the portrayal lacked conviction. Mehta has a screen presence, but as an actor, she still has a long way to go. Despite her flaws, Mehta easily outshines her co-actor Yajur Marwah, the nephew of Krushna Abhishek. Marwah’s lack of confidence could give serious competition to your reviewer when facing the camera.

Tyagi himself unleashed the actor within, portraying not a Sanatani, but the dangerous Maulvi from Murshidabad. He might have converted to Hinduism, but it’s not easy to forget one’s previous identity. While his acting isn’t great, he is undeniably intimidating to watch.

Save for Deepak Kamboj, who played the local leader from Madam Ji’s party, the other actors don’t make much of an impression.

For such a grim story, burdening the script with a needless song feels misplaced. The Diary of West Bengal follows in the footsteps of countless films with stories that needed to be told but lacked the right creative hands. The sight of some viewers leaving early during a special screening doesn’t bode well for its theatrical prospects. West Bengal and its politics will continue to make headlines and fuel noisy news debates, but the odds of cinephiles wanting to open this Diary of West Bengal seem bleak.

Publisher: Source link