Has YRF, Netflix blundered by backing a Maharaj? – Beyond Bollywood

As the controversial film gets mired in a legal battle, we wonder whether this was a gamble worth taking?

By Mayur Lookhar

First, Hamare Baarah then Maharaj. These two films are currently embroiled in legal battles over their release. Hamare Baarah, which was scheduled to hit theaters but has already been delayed by a few weeks, faces allegations of hurting minority religious sentiments. Meanwhile, Maharaj, lined up for a straight-to-digital release, is accused of offending the majority community. The selective echo of compromised freedom of speech is a prevailing concern. More on this later, but let’s dissect the main problem facing Maharaj.

Helmed by Siddharth P. Malhotra and produced by Yash Raj Films, Maharaj was due to be released on June 14 on Netflix. It marks the debut of superstar Aamir Khan’s son, Junaid. Not all star kids rely on typical rom-coms and theatrical releases for their debuts.

Netflix and YRF were hoping to release Maharaj quietly, without any promotion, but now the film faces an uncertain future. The film has been accused of hurting the religious sentiments of the Pushtimarg sect, a Hindu Vaishnav community with strong roots in Gujarat and Rajasthan. The Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Dal has been leading the agitation, with courts in Gujarat and Mumbai ordering a stay. The matter has been pushed till 18 June. The producers and Netflix held a selective press show, hoping that (presumably) positive reviews would build intrigue around the film. The intrigue is there, but now it is due to the stay order on the film’s release. What is it about this Netflix film that is irking members of the Pushtimarg community? If one goes by social media outrage, it is the majority sentiments that are hurting.

Penned by Sneha Desai and Vipul Mehta, Maharaj is a period film based on the Maharaj Libel Case of 1862. Rest assured, millions of civilians, including this scribe, had no inkling of this case. The story goes that led by Jadunath Brijratan Maharaj, key spiritual leaders of the Pushtimarg community filed a libel suit against the Gujarati newspaper Satyaprakash, its editor Karsandas Mulji, and the publisher Nanabhai Rustomjee Ranina for a defamatory article in 1860 alleging sexual exploitation of women by Jadunath and other gurus in the sect. It was alleged that the Sect misled the followers into offering their wives, children to the head of the sect.

Two years later, the Pushtimarg community filed a defamation case against the newspaper. Interestingly, the editor himself hailed from an orthodox Pushtimarg family. Barely two months later, the Bombay Court (earlier Supreme Court) ruled in favor of the journalist. The Pushtimarg community was ordered to pay a fine of Rs. 11,500, but Mulji himself spent Rs. 13,000 fighting the case.

Serious allegations of sexual exploitation by spiritual gurus can never be condoned. However, one cannot discount the fact that the film is set in British India. 162 years later, can people today trust the verdict of the colonizers’ courts? Was this another example of divide and rule? Interestingly, Karsandas Mulji himself was from the Pushtimarg community. Just reading about the case, the plaintiff produced 31 witnesses, whereas the defendant had 33 witnesses. What if there were abstentions and we had a tie? One thing that perhaps went in favor of Mulji is how Jivanlal, the Sect’s Mumbai head allegedly made women sign documents preventing them from criticizing the Maharajs and threatened excommunication.

There can be no moral argument: sexual predators, especially those in religious roles, need to be dealt with seriously and unequivocally. The YRF film is said to be based on author Saurabh Shah’s 2013 book titled Maharaj, which won the Nandshankar Award from the Narmad Sahitya Sabha.

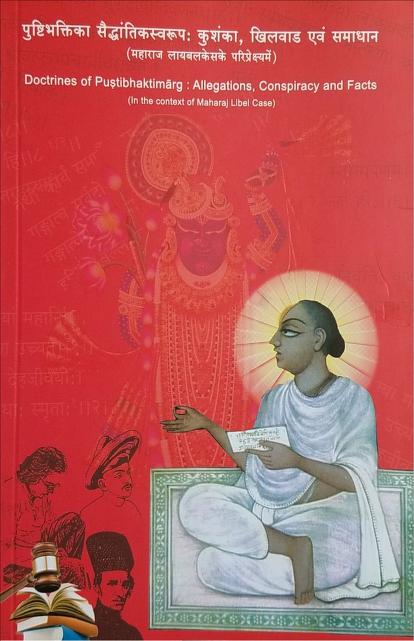

In 2021, a group of writers—Dhawal Patel, Maitri Goswami, Umang Shirodariya, Utkarsh Sharma, Pratyush Mehrishi, and Amit Bhatt—wrote Doctrine of Pushtibhaktimarga: A True Representation of the Views of Sri Vallabhacharya in the Context of the Maharaj Libel Case.

We haven’t read either book, but neither has courted controversy or been banned. Saurabh Shah’s Maharaj perhaps appears to validate the sensational claims made by Karsandas Mulji. Basic information about Dhawal Patel & co.’s book suggests it is based on the true teachings of Pushtimarga founder Sri Vallabhacharya, and possibly offering a balanced perspective on the Maharaj Libel case. Is it whitewashing? It would be naive to suggest such a thing without reading the book.

Is the Netflix and YRF film objective? We may not get an answer until we see it. Given that it is based on Saurabh Shah’s book, one wonders if the producers have considered other perspectives. Both Maharaj and Doctrines of Pushtibhaktimarga: A True Representation of the Views of Sri Vallabhacharya in the Context of the Maharaj Libel Case were written over 150 years after the original case, long after anyone directly involved would have been alive. Their source material would therefore likely come from archives such as Satyaprakash articles or other contemporary papers, or oral histories passed down through the community.

We came across an opinion piece by veteran former lawyer A.G. Noorani in 2015 titled Godmen and Libel that gives us a sense of what transpired in the court. Noorani thanked historian P.B. Vacha of Bombay Bar, who mentioned this case in his book Famous Judges, Lawyers and Cases of Bombay: A Judicial History of Bombay during the British Period, which was launched on the occasion of the centenary of Bombay High Court in 1962. Noorani bought a full record of the Maharaj Libel Case four decades ago for the princely sum of Rs. 15.

It must be noted that Jadunath Brijratan Maharaj had filed a suit for libel on August 15, 1861, citing Karsandas Mulji, the editor, and Nanabhai Rustomjee Ranina, the printer, as defendants. Their trial began on December 12, 1861, and ended with the conviction of the defendants, who then moved the Supreme Court of Bombay.

The Maharaj Libel case was presided over by then Chief Justice Matthew Sausse, a man known for his judicial temper, and Sir Joseph Arnould. The alleged sexual exploitation by the Hindu sect was akin to what was known in Roman Law as jus primae notis (right of the first night), whereby feudal lords felt entitled to have sexual relations with the wives of their subordinates.

The Hindu sect was represented by Sir Thomas Erskine Holland, while Mulji was defended by T.C. Anstey, a man who had once appeared for the Wahabis, who had killed a judge on the steps of Calcutta’s Supreme Court. One Dr. Bhau Daji had defended Jadunath, stating that the religious leader had venereal disease. Nearly two months later, Chief Justice Sausse and Arnould dismissed the plaintiff’s libel case, but the court couldn’t prove the criminality of the religious gurus.

Justice Arnould is said to have said this, “The Maharajas, the hereditary high priests of the Vallabhacharyan sect are, in respect of the practices denounced in the libel, virtually amenable to no jurisdiction, spiritual or temporal, criminal or civil.

“As there was no available spiritual tribunal, so neither was there any criminal or civil tribunal which could take cognizance of these immoralities of the Maharajas. It was profligacy, it was vice, but it was not crime, it was not civil wrong, of which they were accused. There was no violence; there was no seduction. The wives and daughters of these sectaries, (with their connivance in many cases if not with their approval), went willingly—went with offerings in their hands, eager to pay a high price for the privileges of being made one with Bramha by carnal copulation with the Maharaj, the living personification of Krishna.”

This implied that the court’s order was solely to dismiss the libel case, as it lacked the authority to prosecute the alleged culprits. If Jadunath and other alleged sexual predators were not convicted, is it then wise for a filmmaker and producer to make a film on such a subject 162 years later?

No one is above the law today, but it’s never easy to bring powerful, influential people to justice. It’s hard to comprehend how men like Asaram and Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh managed to build cult followings. These are men convicted of rape and other serious charges, yet they often receive parole during periods preceding electoral polls. Director Apoorv Singh Karki delivered a brilliant film in Sirf Ek Bandaa Kaafi Hai [2023], loosely based on Asaram’s case. What is shocking is that to this day, these convicted fake godmen continue to garner support, at least on social media.

Bandaa was initially released on OTT platforms, but buoyed by positive reviews and digital response, the makers opted for a limited theatrical release. Unfortunately, the box office returns were not impressive. Setting aside the controversy, would viewers who watched Bandaa be interested in a similar story on Netflix? The current socio-political environment may still not be conducive for such narratives.

Did YRF and Netflix forget what happened with Amazon Prime Video over the series Tandav? Were the producers expecting a change in the socio-political environment following the Indian General Elections? Even if the incumbents did not retain power, a new liberal establishment would likely have faced criticism for promoting an alleged anti-Hindu film. If they were to regain power after ten years, it’s uncertain if secular, liberal parties would take such a risk.

India is currently in a phase where the majority population takes pride in its cultural roots. Noted American-Indian journalist Fareed Zakaria also believes that this isn’t necessarily a negative development. In this current environment, a film like Maharaj would naturally be seen as anti-Hindu propaganda.

Though a marquee name in Bollywood, Yash Raj Films hasn’t had the best time in the last few years. Excluding Pathaan [2023], they have endured a disastrous period. What is surprising is that YRF faced similar criticism with Shamshera [2022]. This reviewer remembers how even a nationalist critic stormed out of the press show, condemning Shamshera as an anti-India film. Personally, director Karan Malhotra had the right intentions with Shamshera, but it suffered due to poor execution.

YRF had drawn criticism for trivializing female infanticide in Jayeshbhai Jordaar [2022], followed by The Great Indian Family which saw its protagonist facing an identity crisis akin to Sai Baba. Tiger 3 [2023] was labeled a pro-Pakistan film, and now there is Maharaj. The storylines and sequence of these films from YRF have clearly irked Hindu nationalists, who smell anti-Hindu propaganda.

Netflix, too, has incurred their ire with content like Leila [2017] and Annapoorani [2023], the latter of which had to be pulled down. So, why approve Maharaj when you know it’s bound to create controversy? Surely, these bigwig producers and networks are not banking on controversy to drive their platform.

What about first-time actor Junaid Khan? We recall Aamir Khan saying in a video that today’s kids don’t listen to their parents. Given the trolling Aamir continues to face for hurting religious sentiments in pk [2014], didn’t he caution his son that choosing Maharaj as a debut film could backfire? Aamir’s son playing the lead in Maharaj has given more ammunition to the Hindu nationalists and #BoycottBollywood brigade to target the father-son duo. There’s a real danger that Junaid’s first film might not see the light of day. If the usual nepotism barb wasn’t enough, young Junaid has potentially harmed his career by choosing Maharaj. While some may applaud the makers for their courage, if the courts were to ban the film, words of encouragement won’t compensate for the huge losses.

Now, at the other end of the spectrum, we have the little-known film Hamare Baarah by filmmaker Kamal Chandra, starring veteran actor Annu Kapoor in the lead role. This is a story that addresses population explosion, with the main character being a Muslim man with nearly a dozen children. It’s interesting how such content is labeled as propaganda by Left-Liberals. If hurting religious sentiments is considered propaganda, then the same yardstick should apply when films like Annapoorani and Maharaj come around.

Despite its poor production values, labeling The Kerala Story [2023] as a propaganda film was unjustified. Are the grievances of women from Kerala any less significant than those of women from the Pushtimarg community in 19th century? Whether willingly or unwillingly, religious conversion through marriages should be criminalized. It would be hypocritical for those who condemned The Kerala Story to praise Maharaj.

Trolling should never be encouraged, but it’s important to acknowledge that this resentment against Bollywood has been building up over several decades. In a different era and social-political environment, Bollywood glorified invaders. What is particularly shocking is how certain filmmakers have been so captivated by the Aman Ki Asha narrative that they found it acceptable to demonize a former Indian soldier. Farah Khan’s Main Hoon Na [2004] and YRF’s Pathaan [2023] are examples of this. Portraying Jim [John Abraham] siding with the arch-enemy makes him a villain, but viewers are still taken aback by how Farah Khan depicted former Indian soldier Raghavan [Suniel Shetty] as someone trying to disrupt the fictitious Indo-Pak peace meet.

Bollywood and other film industries have long been suspected of immoral practices like the casting couch. Critics of Maharaj will therefore challenge Bollywood producers to first clean its own house.

While Hindu nationalists have legitimate grievances, advocating for a ban on Maharaj yet simultaneously supporting films like Hamare Baarah, 72 Hoorain, or the upcoming The Diary of West Bengal reeks of hypocrisy. We oppose any form of ban; it’s the duty of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) to oversee content. Some years ago, CBFC chairman Prasoon Joshi emphasized the importance of respecting sentiments across all faiths. Whether CBFC has been consistent in this policy remains a matter for another day.

Each film needs to be viewed in its context. You support a Kerala Story, but you don’t care for the victims in a Maharaj. There can never be a comprise on any woman’s dignity. Given how women safety continues to be a pressing issue in India, as citizens we must lend an ear to cries of women in films like Maharaj.

We hope the courts take an objective view on Maharaj. Just like Karsandas Mulji, it seems that YRF, Netflix, and Siddharth P. Malhotra are facing a similar predicament.

There was uproar before Pathaan too, when ultra nationalists took offense to Deepika Padukone’s saffron bikini in the song Besharam Rang. Despite all the commotion and threats, everything settled down just two days before Pathaan’s release. Contrary to rumoured cuts, the saffron bikini received ample screen time. However, both nationalists and Left-leaning critics who cheered it, failed to grasp the context of an ISI female agent wearing a saffron bikini.

Is it possible that all this uproar over Maharaj could eventually turn out to be a PR stunt? Well, with the matter now in the courts, that theory seems unlikely.

Come 18 June, whatever the court decides, we will respect its verdict. God forbid, If the courts doesn’t rule in the favour of the defendants, then Netflix, Yash Raj Films would have committed a blunder in making a Maharaj.

Publisher: Source link